Note: This post was motivated by the comedian Rob Delaney’s twitter comment that Obamacare will help satisfy the base of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which will lead to a stronger economy. This idea has an intuitive appeal, so I decided to flesh out the argument in a longer format than twitter allows.

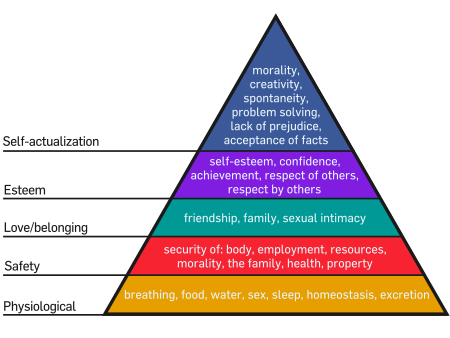

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, first proposed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,” is often illustrated as a pyramid like the one above. The idea is that human beings will not be able to focus on satisfying their higher level needs, such as creativity and respect, until they have satisfied their most basic needs, like food and sleep. Once they have taken care of their physiological needs, they can move on to worrying about their safety needs; once those have been met, they move on to their love/belonging needs, and so on.

Economists have already shown that economic growth can help people reach higher levels on the pyramid (The Wealth of Nations Revisited: Income and Quality of Life, 1995). This makes sense because as national income grows, people can afford to buy more food, water, housing, and other basic necessities. Rich nations can afford to build sanitation systems and basic infrastructure that people depend on to pursue their life goals. Clearly, causation runs one way, but it does it go the other way too? In other words, if the government were to design its domestic policy to meet all the physiological and safety needs of its citizens, then would its labor force be more productive?

A cursory look at the world GDP per capita rankings, as determined by the World Bank, reveals much about what types of policies might lead to higher productivity (GDP per capita is a measure of productivity). In the top ten, there are five countries that can aptly be described as social democracies, i.e. countries whose governments provide generous, universally-accessible public services, including education, health care, child care, and workers’ compensation. These five countries are Norway, Australia, Denmark, Sweden, and Canada. The other five are very small countries that depend on a single industry for outsized incomes. There are the petrostates, Kuwait and Qatar; the financial centers and international tax havens, Switzerland and Luxembourg; and the East Asia gambling mecca, Macao. If the United States, currently ranked 14th, wants to improve its workers’ productivity, it should look to the five large countries, rather than anomalous small countries, for guidance.

Note that all I have shown so far is that there is a correlation between GDP per capita and the level of public services provided by the state. Some people might even argue that a few of the social democracies would be more appropriately placed in the “anomalies” category. There is an argument to be made that Australia’s wealth is derived from the combination of its abundant natural resources and China’s insatiable thirst for raw materials. But then again, maybe not. The Scandinavian countries have their fair share of natural resources as well, not least among them oil, so maybe that’s how they manage to fund a generous welfare state while maintaining a high GDP per capita.

To make the case for causation, we need to examine one of the basic principles of economics: risk aversion. Economists observe that in the presence of uncertainty, people are usually risk averse, meaning given the choice between investing in a risky investment with a high rate of return and a less risky investment with a relatively lower rate of return, they will choose the less risky option. This risk aversion is compounded by the relatively new discovery from behavioral economics that people have a loss aversion bias, which means they care more about preventing losses than acquiring gains. For example, one study showed that if you want to motivate students to perform well on tests, you should give them the reward before the test and then threaten to take it away if they fail to achieve a certain score. The study found that this incentive is more powerful than telling the students they will be given the same reward after the test is completed if they meet the threshold.

So people inherently don’t like taking risks and they don’t want to lose what they already have. This presents a clear and present danger to economic growth, as most economists believe entrepreneurship, also known as risk taking, is an important driver of innovation and increases in productivity. To help illustrate this theory, let’s consider the hypothetical case of Joe the Plumber. Let’s assume Joe works 40 hours a week at a mid-sized plumbing company in Cleveland, Ohio. Joe currently makes enough money to feed his family of four, maintain their health insurance coverage, and save for his kids’ college education. Now suppose that Joe wants to start his own plumbing company. To do this he will have to take business classes at a community college, take out a loan from the bank, and decide which tools, office space, technology, and transportation to invest in, just to name a few. Joe will also have to devote a lot of time to working on the new business, so he will need to spend more money on child care services. If this business were to fail, it would be a serious financial hardship for Joe’s family and he would have to discontinue the family’s health insurance and stop adding to his children’s college funds. Not wanting to lose what he already has by taking unnecessary risks, Joe forgoes the opportunity to start his own business. The economy stagnates.

But if Joe were to start his business in say, Norway, he wouldn’t have to worry about many of these downside risks. His whole family would be entitled to health care, education, child care, and other public services, no matter the fate of his new business. What does Joe do then? He takes the plunge and signs up for business classes, knowing that failure won’t irrevocably harm his family. The economy now has one more entrepreneur hoping to strike it rich. If he succeeds, the economy will grow larger than it otherwise would have been able to.

Now many would argue that the possibility of grave personal financial hardship is an important motivator for a businessman to succeed. This may be true on some level, but let’s not exclude the other reasons people start businesses. Being the owner of your own business merits a certain level of respect in the community and gives you a sense of achievement that is difficult to find elsewhere. Furthermore, a successful business would undoubtedly boost its owner’s confidence and self-esteem. There are myriad reasons to work toward making a business successful, aside from avoiding personal financial catastrophe.

This simplification is not meant to be a dispositive example of the effects of social democracies on economic growth in all cases, or that the total economic benefits of a large welfare system outweigh the total economic costs. I merely wanted to show that by securing the lowest levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it is possible there will be more, not less, economic growth than without doing so. Indeed, there seems to be much evidence to recommend this framework for domestic policy and proponents of a stronger welfare state would stand to benefit from adopting it.

The welfare ghettos should be a hot bed of entrepreneurs. Oh wait, they are. Some very sophisticated drug networks spring up!

Just kidding you Alec. I love your writing and thinking. Most successful people have failed at some point in their lives at something. But they have perseverance and try until they get it right.

I have no doubt that you will be successful, but if you do hit a hic up…..you know what to do. :o)