Education is said to have positive externalities. That means there are significant benefits to people who are external to the exchange between teacher and student. Even though teachers are the only ones who are paid to educate students and students gain human capital by attending school, conventional wisdom holds that society as a whole benefits from having a more educated citizenry. A quick look at the available data shows that people with more education are less likely to be unemployed and can expect to receive a higher income for their work. Higher incomes means higher tax revenue for the government and more disposable income for the people who earn them. Now, though these data merely show a correlation between education and employment benefits, there are many reasons to believe there is causation as well. Even if you don’t think high school and college actually increase the knowledge of students (there are skeptics), it is a fact that many recruiters focus their time and resources on college campuses and that lots of jobs require a certain degree to even apply (this is known as credentialism).

But these are just the most common arguments for why investing in education is worthwhile. If those haven’t fully succeeded in convincing taxpayers that their money is being well spent, what else can be said to persuade them? One of the basic assumptions of economics is that people are self-interested and will only do what is best for themselves. While this is clearly a gross simplification, a few hours of interaction with most people will tell you this is at least on target. So if you want to increase public investment in education, you must make a more convincing argument for its positive externalities, i.e. the value for everyone apart from the students and teachers. This is where Condorcet’s jury theorem comes in. In short, the theorem is concerned with determining the probability that a group comes to a correct decision under majority voting. If the probability (p) of an individual in the group voting for the correct decision is greater than 1/2, then adding people to the group will make it more likely the group will come to the correct decision. Conversely, if p < 1/2, then adding more people to the group will only decrease the likelihood of the group reaching the correct decision (in this case the optimal number of voters would be 1). Now, political scientists say that Condorcet’s jury theorem provides a theoretical basis for democracy, but they often overlook the importance of the assumption that p > 1/2. If it is not, the theorem dooms democracy rather than provides a basis for it.

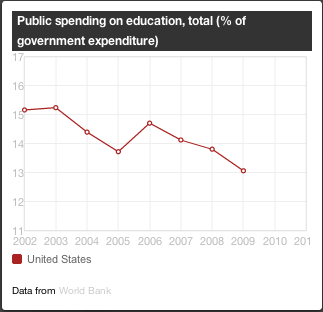

The key here is that there is a tipping point. If p is less than 1/2, with a population of more than 300 million people, we are fated to choose suboptimal outcomes. But once p passes the 1/2 threshold, the reverse begins to hold true: we are extremely likely to make the correct decision, i.e. choose good public policy. I believe that if we improve our education system, we can increase p dramatically. When people have taken classes in Economics, Finance, English, Math, Science, etc., they are better prepared to challenge harmful policies and their proponents. More educated citizens will also be more well-equipped to analyze ballot propositions and the positions of candidates for public office. Education reformers disagree about how to best improve our education system, but if we begin to realize how important it is to the quality of our democracy, our policymakers will devote more time to answering these questions. Until then, we should pursue an “all-of-the-above” approach, preferably through randomized field trials. Just to name a few options, we could increase government funding (see chart below), improve school choice, and incorporate new technology into classrooms. Once we determine which of these approaches is the most cost effective, we should devote more resources in that direction.

Unfortunately we don’t seem to be doing very well on the “increasing funding” part. In fact, we are doing the opposite:

So the next time someone says we shouldn’t prioritize education, refer them to Condorcet’s jury theorem and ask them how we can afford not to.